An examination of pertinent and under researched issues related to the growing use of mindfulness meditation (MM) and other contemplative practices in health care starts with discussions of the common understanding of mindfulness developed by John Kabat-Zinn’s (1994) who famously defined it as – “paying attention in a particular way, on purpose, in the present moment, non-judgmentally” (p.4). Changing understandings of mindfulness, now impacting how it is taught and practiced, start with the differentiation of MM and Mindfulness Based Interventions (MBI). MM practices are generally grouped into two primary types: focused attention and open monitoring (Vago & Silbersweig, 2012). MBIs, although often incorporating MM practices, generally do so within a larger collection of therapeutic techniques. The most common MBIs are Mindfulness Based Stress Reduction (MBSR) (Kabat-Zinn, 1990), Mindfulness Based Cognitive Therapy (MBCT) (Segal, Williams, & Teasdale, 2002), Dialectical Behavioral Therapy (DBT) (Linehan, 1993), and Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT) (Hayes, Strosahl, & Wilson, 1999). This under researched issue introduces a number that are currently arising, which challenge the rapid adoption of contemplative practices such as MM.

0 Comments

I was recently introduced to this organization, Frontline Yoga, which is helping veterans and front-line support people such as the Police and nurses and doctors in emergency wards - who are suffering trauma because of their work. It looked like a great initiative to me: http://www.yogaforthefrontline.com/ And this is their Facebook site, there are some inspiring stories on it: https://www.facebook.com/FrontlineYogaFoundation/?fref=nf From their website: "Frontline Yoga Inc. delivers Trauma Aware Yoga to members at the Frontline. Police, Paramedics, Firefighters, Defence, Healthcare Workers, SES/RFS and Surf Life Savers are able to access free weekly Yoga. Our aim is to foster community and support, develop mental and physical strength, build resilience, a sense of peace and tools for self-regulation in order to optimise the processing of occupational stressors.  Andrew Olendzki: "Consciousness, Non-Self and Contemplative Art: Buddhist Influences on a New Art Movement." Video of a presentation given at Smith College in Northampton, MA on August 5, 2015. There are a number of interesting video presentations on different aspects of Buddhism presented by the Buddhist scholar Andrew Olendzki, scroll down to the bottom of the page to see the one on Contemplative Art through a Buddhist lens: http://www.andrewolendzki.org/video.html I have recently been introduced to the idea of a trauma informed approach to contemplative practice not only in Contemplative Education but in all uses of contemplative practice. This is link to a short video on trauma informed yoga: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=f_mBp5p6h2M

I was recently introduced to this idea of: Second Generation Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction Interventions, I'm not sure if it quite does what is outlined in this quote from Shonin and Van Gordon but its a great start to remediating the issues related to stripping Buddhism out of some of the foundational practices in MBSR. Shonin, E., & Van Gordon, W. (2015). Managers' experiences of meditation awareness training. Mindfulness, 6, 899-909. “Due to the suggestion that some individuals may prefer to be trained in a version of mindfulness that more closely resembles a traditional Buddhist approach, recent years have witnessed the development and early stage evaluation of several Second Generation Mindfulness-Based Interventions (SG-MBIs; Singh et al. 2014). Although SG-MBIs still follow a secular format that is suitable for delivery within Western applied settings, they are overtly spiritual in aspect and teach mindfulness within a practice infrastructure that integrates what would traditionally be deemed as prerequisites for effective spiritual and meditative development. At the most basic (but by no means the least profound) level, such prerequisites include each element of the Noble Eightfold Path. The Noble Eightfold Path comprises each of the three quintessential Buddhist teaching and practice principles of (1) wisdom (i.e. right view, right intention), (2) ethical conduct (i.e. right speech, right action, right livelihood) and (3) meditation (i.e. right effort, right mindfulness, right concentration). Each of these three fundamental elements (Sanskrit: trishiksha—the three trainings) must be present in any path of practice that claims to expound or be grounded in authentic Buddhadharma, and they apply to (and form the basis of) the Fundamental or Theravada vehicle just as much as they do the Mahayana and Vajrayana Buddhist vehicles. Thus, for mindfulness practice to be effective, it must be taught as part of a rounded spiritual path, and it must be taught by a spiritual guide that can transmit the teachings in an authentic manner (Shonin et al. 2014; Shonin and Van Gordon 2014)." (Shonin and Van Gordon, 2015, p. 900 ) References: Singh, N. N., Lancioni, G. E.,Winton, A. S.W., Karazsia, B. T.,& Singh, J. (2014a). Mindfulness-based positive behavior support (MBPBS) for mothers of adolescents with autism spectrum disorders: Effects on adolescents’ behavior and parental stress. Mindfulness. doi:10.1007/s12671-014-0321-3. Shonin, E., Van Gordon, W., & Griffiths, M. D. (2014a). The emerging role of Buddhism in clinical psychology: Towards effective integration. Psychology of Religion and Spirituality, 6, 123–137. Shonin, E., & Van Gordon, W. (2014a). The lineage of mindfulness. Mindfulness. doi:10.1007/s12671-014-0327-x. Developments in Contemplative Education at Atma Jaya Yogyakarta University, Yogyakarta, Indonesia29/4/2016 I have a wonderful friend and colleague Prasasto Satwiko a professor of Architecture in the Faculty of Engineering at Atma Jaya Yogyakarta University (AJYU), Yogyakarta, who since 2010, has supported the integration of yoga into classes in his faculty. This started with the use of yoga and meditation in an Art History class. He and his colleagues were gratified to see that these students were enthusiast about the yoga classes and from 2012-14, 80 students and 8 assistants have successfully taken part in the classes. Because of the success of these courses yoga has now became an integral part of their design studies. This started formally in semester 2, 2015 and they now have yoga integrated into Design Studio 1-6 with 10 parallel classes. The increasing interest in contemplative practice at AJYU links with the university's declaration to be a ‘green and healthy campus’. As a part of this initiative AJYU now has the vegan restaurant Veganissimo on campus.

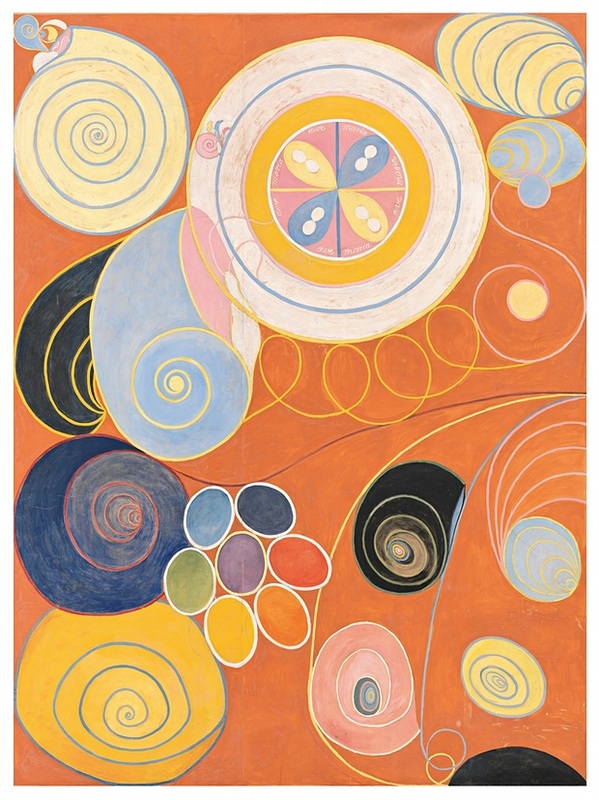

I am pleased to announce the publication of “Contemplative practice in the law school: Breaking barriers to learning and resilience” and my co-authored chapter with Professor Vines: Contemplative practice in the law school: breaking barriers to learning and resilience: The Abstract In this chapter we argue that the increasing use of contemplative practices in law schools is significant not just in relation to enhancing resilience and diminishing stress and depression, but that they also have major benefits in the development of traditional legal roles. However, there is an attitudinal barrier that needs to be overcome as law students and legal academics have commonly been resistant to the use of these practices. It is interesting and somewhat ironic, therefore, that just as we are developing some level of openness to practices that seem alien in legal study and practice we also find evidence that they indeed enhance capacities for legal and educational practice such as level of focus, ability to prioritize, the optimization of objectivity, higher order thinking and so on. Further, the management of ethical issues of professional practice, which are frequently triggers for depression, may also be improved by contemplative practices as they enhance students’ and lawyers’ ability to articulate their personal and professional ethics. In turn, this knowledge can be used to help break down remaining barriers to the use of contemplative practices within the legal academy. To reiterate, until recently the supposition was that the remedial benefits of contemplative practices ameliorated negative aspects of legal education and practice. However, now it appears that the enhancement may also be linked to a direct correspondence between contemplation and the law. For more information please see: For more information please see: https://books.google.com.au/books?id=jzz7CwAAQBAJ&printsec=frontcover&source=gbs_ge_summary_r&cad=0#v=onepage&q=Patricia%20Morgan&f=false  I was recently sent information about two great educational initiatives in Australia: The first from Tony McKenzie, which has two parts first his: Blog about learning and teaching in the twenty-first century titled: One giant learning curve for humanity (http://tonymckenzie.wix.com/learning-curve). And the other is a project called ‘i witness’ being mounted by local community group, Orange CultureHub; see http://orangeculturehub.wix.com/joinus#!i-witness/wu6nx. And John Turner's Quiet Kit, he says: I recently launched QuietKit ( http://quietkit.com/ ), which helps people get started with mindfulness and meditation, as well as helps them build a meditation habit, all for free. It's already helped a number of people deal with stress, and I'm hoping to reach many more. John Turner Founder, QuietKit http://quietkit.com/ ( http://quietkit.com/ ) The Quiet Kit helps individuals Learn to increase focus, reduce stress, and increase mindfulness with simple guided meditation for beginners.  The Contemplative Pedagogy Network, UK, has a blog page listing a number of interesting posts the most recent being one on 'Exploring Labyrinths' and the preceding post which reflects on the question: 'Is telling students to be compassionate enough?' To read these posts go to: http://contemplativepedagogynetwork.com/ If you're going to be in Scotland in April their events page is currently listing the Growing Contemplative Practices in Higher Education?Queen Margaret University, Edinburgh, EH21 6UU, Scotland, Friday 22nd April 2016, 9am-4.30pm, See: http://contemplativepedagogynetwork.com/events/  This article in the Guardian engages with Hilma Klint's Visionary Art, starting with this question: "Was Hilma af Klint Europe’s first abstract artist – before even Kandinsky and Mondrian? As an exhibition of her extraordinary, occult-inspired works opens at the Serpentine Gallery, London, we travel to Sweden to find out" http://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2016/feb/21/hilma-af-klint-occult-spiritualism-abstract-serpentine-gallery |

Author: Dr Patricia Morgan

I am a teacher, contemplative practitioner, researcher, community developer and artist, currently working in the area of Contemplative Education, which I believe is one of the most important movements in education today. Categories

All

Archives |