4 Insights

In this last section I’d like to offer 4 insights about Contemplative Education that I have gained over the past 7 years of my research in this area. They are important to consider when developing sound contemplative education initiatives:

Insight 1: Interdisciplinary Engagement with Contemplative Education is important

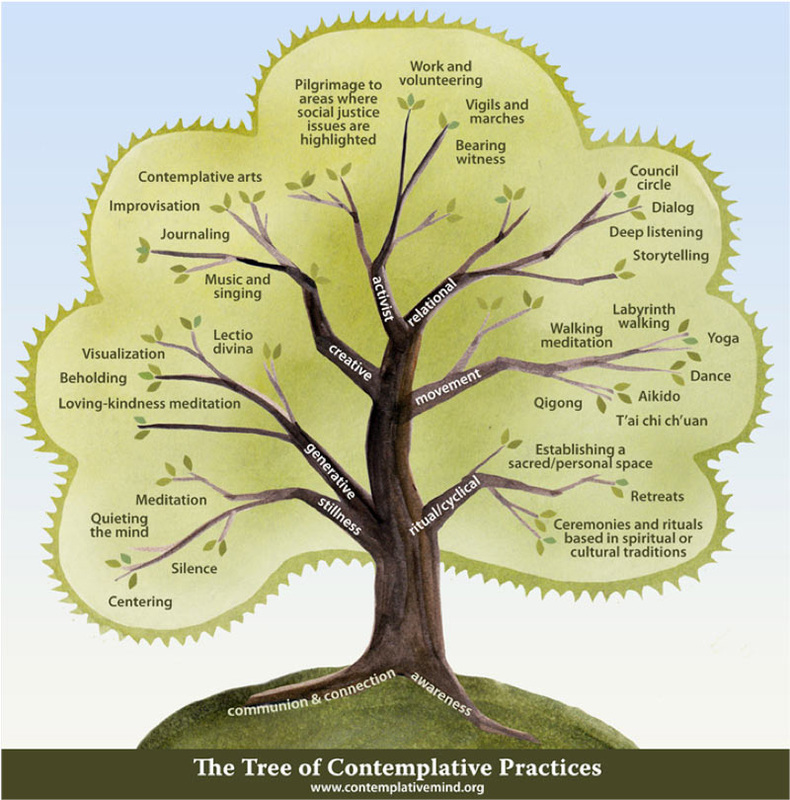

I believe it’s important to take an interdisciplinary approach when developing Contemplative Education initiatives. Both the human and life sciences need to be equally represented to provide a holistic approach in which the insights and methods from the arts and humanities inform those of the life sciences. Integral to this is a comprehensive understanding of contemplative practice, as opposed to a concentration on just one, which is currently happening with mindfulness and mindfulness based stress reduction or MBSR. The problem with the focus on, and commodification of MBSR (while a great practice), is that it can become quiet improvised and easily commercialised as can be seen where it is now being labelled ‘McMindfulness’. Hyland (2015) in his discussion of this issue laments “as often happens with popular innovations, the burgeoning interest in and appeal of mindfulness practice has led to a reductionism and commodification – popularly labelled ‘McMindfulness’” (p. 1). Plus there are dangers for those who engage practices stripped of their origins, when they, through the practices, begin to ask some of the big questions, such as ‘Why am I here’? or ‘What are my values’? For the answers, devised across centuries of theoretical and empirical research by the wisdom traditions that supply the practices, won’t be directly available. I believe the Tree of Contemplative Practice from the CCMIS provides a good overview of the many practices available to choose from in our pedagogical innovations.

The Center for Contemplative Mind in Society’s ‘Tree of Contemplative Practices’ (http://www.contemplativemind.org/practices/tree)

Insight 2: Contemplative Approaches Need to be Integrated into the Curriculum

There are many worthwhile places in the co-curricular space for contemplative education initiatives, though for a comprehensive approach to Contemplative Education it is necessary for it to be integrated into curriculum and span disciplinary fields. When doing this the practices used, should be relevant to the course not just an ‘add on’, this also means they have to be assessable, and suitable evaluation methods used. Implicit in this is an ethics of care required when working with psychologically influential practices that can take individuals into subjective or emotional realms that they may not be familiar with. In addition is the understanding of developing contemplative pedagogy in relation to the progress of a course of study.

There are numerous fine examples of such courses though I’d like to mention one that I’ve worked on, which is the ‘Introduction to Law and Justice’ course, developed by Professor Prue Vines at the School of Law, UNSW. I’ve lectured with Prue in the course introducing contemplation through theory and practice. The section of this course in which contemplative practice is introduced is ‘development of personal and professional identity in law’.

Contemplative theory and practice is presented in a lecture on resilience for the first year students and then they are led through short practices in the first four of the seminar style classes that comprise the course. After this induction the students are asked to practice their contemplative and reflective skills at home and in a ‘court observation’ leading to a report.

There are numerous fine examples of such courses though I’d like to mention one that I’ve worked on, which is the ‘Introduction to Law and Justice’ course, developed by Professor Prue Vines at the School of Law, UNSW. I’ve lectured with Prue in the course introducing contemplation through theory and practice. The section of this course in which contemplative practice is introduced is ‘development of personal and professional identity in law’.

Contemplative theory and practice is presented in a lecture on resilience for the first year students and then they are led through short practices in the first four of the seminar style classes that comprise the course. After this induction the students are asked to practice their contemplative and reflective skills at home and in a ‘court observation’ leading to a report.

|

For a comprehensive approach to Contemplative Education it is necessary for it to be integrated into curriculum and span disciplinary fields. When doing this the practices used, should be relevant to the course not just an ‘add on’, this also means they have to be assessable, and suitable evaluation methods used.

|

They are required to visit a court and report on what they observe, including whether the lawyers and judges appear to have a personal system for dealing with difficult situations. The aim here is to draw on the students’ understanding of the metacognition that can develop through contemplative practice, which they learnt about previously. In addition there is an essay in the final exam on contemplative practice as it is relevant to personal and professional identity and the metacognition that can lead to good exercise of judgment.

|

Insight 3: Contemplative Education Links with Other Holistic Approaches in Education

When developing contemplative pedagogy it is important to understand and engage the connections between Contemplative Education and contemporary holistic approaches in Education that aim, in various ways, to address problems that have arisen from Cartesianism. These approaches include: Somatic and Affective Education, Integral and Transformative Education, Pro-sociality, Enactivism, Positive Psychology, Mindful Leadership and Emotional Intelligence. Each, to some extent, requires heightened self-awareness, which is what links them to Contemplative Education. However, it is only recently that theorists and pedagogues working in these areas have moved from theory to practice, as they address experiential embodied ways to develop increased self- and other awareness. A number of these theorists are now developing methods to integrate contemplative practice into their speciality areas.

|

It is important to understand and engage the links between Contemplative Education and: Somatic and Affective Education, Integral and Transformative Education, Pro-sociality, Enactivism, Positive Psychology, Mindful Leadership and Emotional Intelligence.

|

For example the educational philosopher Andy Begg (2013) speaks about the links between contemplation and Enactivism, outlining, I believe, the site of linkage between contemplation, enactivism and the other approaches mentioned above. In doing this Begg differentiates between ‘knowledge’ and ‘knowing’, knowledge meaning to possess facts, and knowing - ‘being with insight’. Important with the latter is a sense of knowing one’s self, which also means knowing our relationship with the world, which as Begg asserts is a part of our essential being.

He concludes his alignment of Enactivism and contemplation by saying, “I think it is of extreme importance because it is largely though contemplation and direct insight that we come to see the connectivity of self and others, and the world - and then begin to see knowing and being as the same” (2013, p. 92). |

Begg’s point related to direct insight highlights the intersubjectivity that can arise in contemplation. This is important to understand when designing contemplative pedagogy, as the heightened sense of others often experienced as intersubjectivity and termed second-person consciousness can lead to changes in students’ values and ethical engagement in the world. It is something that Parker Palmer alludes to here when speaking of contemplation:

|

…it offers a powerful corrective to the chain of philosophical errors that has loosed too many amoral and even immoral educated people on the world. That corrective involves “contemplative practice”…[contemplative pedagogy]…helps students focus more intently on subjects ranging from physics to literature, connect as whole persons with what they are learning, and feel more keenly their responsibilities as educated persons in the larger ecology of human and nonhuman life (Palmer, in Barbezat, D. & Bush, M., 2014, p. viii).

|

Insight 4: There is a Need to Acknowledge First and Second person Experience in Education

The fourth insight relates to the need to acknowledge and engage first and second-person experience in education. My realisation of this developed through the course of my PhD where I observed the way contemplation provided access to first-person or subjective consciousness and second person or intersubjective consciousness. This aspect of students’ experience appeared to found their making of new meaning both personal and in relation to their courses of study. However, the problem is that these stages of learning are subtle and fragile and tend to dissolve when exposed to words, which is why the first-person in particular is often deemed ineffable or un-wordable. This and the politics of subjectivity are, I believe, why its presence is assumed but passed over in education, where the drive is for 3rd person or objective, rational acquisition of knowledge. The importance of second person or intersubjective states of consciousness (Gunnlaugson, 2011) is being acknowledged along with embodied and affective ways of knowing and learning, but the rich and foundational nature of subjective or first-person learning, which can be directly accessed through contemplation, has yet to be embraced in mainstream education.

I addressed this issue in the research I conducted at the Mind and Life Institute Massachusetts at the beginning of 2015. In this research I trialled interviewing participants directly after meditating together, so that we were both in a similar state of consciousness. I did this to engage the intersubjectivity that can arise when meditating together, as I believed this would provide richer data and therefore more nuanced information about participants’ subjective experience. This is what happened as the data from these interviews was very rich. One of the people I interviewed was Richard (a pseudonym) a 21 year old Maths student at Amherst College, Massachusetts. In the interview he recalled a strong somatic contemplative experience saying:

I addressed this issue in the research I conducted at the Mind and Life Institute Massachusetts at the beginning of 2015. In this research I trialled interviewing participants directly after meditating together, so that we were both in a similar state of consciousness. I did this to engage the intersubjectivity that can arise when meditating together, as I believed this would provide richer data and therefore more nuanced information about participants’ subjective experience. This is what happened as the data from these interviews was very rich. One of the people I interviewed was Richard (a pseudonym) a 21 year old Maths student at Amherst College, Massachusetts. In the interview he recalled a strong somatic contemplative experience saying:

|

Richard: “There’s a lot of activity in my head area, or my brain and for me a lot of my baggage or junk seems to be somatically stored in there and in my heart area. In the first 10 day silent retreat I went on there was a lot of burning and pain in that area, there was this intense rage – psychosomatically that had been stored in my body”.

Patricia: What does that feel like to you? Richard: “It’s like burning, and I see like red or pus yellow or like dark – it feels like sludge”, and as Richard was speaking he held the area over his heart. (Interview, March, 2015) |

One way to understand this might be through the neuroscience and meditation research of

Catherine Kerr, at Brown University’s Medical School in the US. Kerr’s (2012) investigation of the Body Scan (a contemplative somatic practice from Mindfulness Based Stress Reduction) has led to her proposition that the subtle sensory focus, which can develop through it, has implications for learning and the treatment of depression. Her findings relate to two brain networks in the prefrontal cortex and the way that they can be controlled or entrained by contemplative somatic focus. They’re the medial prefrontal cortex network, which is associated with rumination and self-judgement and the lateral prefrontal cortex network, which is associated with attention and positive affect. Kerr found that the body scan can, as she terms it, ‘turn up’ the volume on the lateral prefrontal cortex network, which in effect turns down the volume on the medial prefrontal cortex network, or turns down the rumination that can lead to anxiety and depression. Kerr believes this is due to the way that somatic contemplative practice interfaces with the workings of the thalamocortical circuit, which sits beneath the cortex and acts as a gatekeeper for sensory input.

Kerr’s findings may help explain the physiology of Richard’s experience, but does it clarify his first-person experience of this physiology? While I find Kerr’s work very interesting and in general the past 40 years of neuroscience and meditation research has validated the field I work in, it doesn’t help me explain why Richard coloured the feelings he had in his heart – red and pus yellow. However, when you think about what he said, I imagine you have some sense of what he meant, or at least that his first-person experience was powerful and important to him? Richard’s story illustrates why I believe we need to directly engage first-person experience in education. This requires the identification of methods that can effectively engage the first-person. The results would then inform the development of robust first-person pedagogy.

In Conclusion

Significant here is the question that the educational philosophers Heesoon Bai, Charles Scott and Beatrice Donald ask:

Catherine Kerr, at Brown University’s Medical School in the US. Kerr’s (2012) investigation of the Body Scan (a contemplative somatic practice from Mindfulness Based Stress Reduction) has led to her proposition that the subtle sensory focus, which can develop through it, has implications for learning and the treatment of depression. Her findings relate to two brain networks in the prefrontal cortex and the way that they can be controlled or entrained by contemplative somatic focus. They’re the medial prefrontal cortex network, which is associated with rumination and self-judgement and the lateral prefrontal cortex network, which is associated with attention and positive affect. Kerr found that the body scan can, as she terms it, ‘turn up’ the volume on the lateral prefrontal cortex network, which in effect turns down the volume on the medial prefrontal cortex network, or turns down the rumination that can lead to anxiety and depression. Kerr believes this is due to the way that somatic contemplative practice interfaces with the workings of the thalamocortical circuit, which sits beneath the cortex and acts as a gatekeeper for sensory input.

Kerr’s findings may help explain the physiology of Richard’s experience, but does it clarify his first-person experience of this physiology? While I find Kerr’s work very interesting and in general the past 40 years of neuroscience and meditation research has validated the field I work in, it doesn’t help me explain why Richard coloured the feelings he had in his heart – red and pus yellow. However, when you think about what he said, I imagine you have some sense of what he meant, or at least that his first-person experience was powerful and important to him? Richard’s story illustrates why I believe we need to directly engage first-person experience in education. This requires the identification of methods that can effectively engage the first-person. The results would then inform the development of robust first-person pedagogy.

In Conclusion

Significant here is the question that the educational philosophers Heesoon Bai, Charles Scott and Beatrice Donald ask:

|

Is there a sense that education today is dominated by a certain mood and mode of consciousness that precariously holds up the colossal edifice of modern industrial civilization?” (Bai, Scott, Donald, 2009, p. 320)

|

This mode is typified by 3 central elements: Firstly, the objectification of our bodies, which is a result of being alienated from our fleshy reality. Secondly, a perceptual and sensuous disconnect, founded on the pervasive subject-object divide. The third level of disconnect is the human-to-human where we are detached from interpersonal intersubjectivity. Bai and her colleagues suggest that the mode of consciousness many of us now act out of has resulted from regular experience of these levels of separation.

The outcome for education they suggest is that, “the larger visions of education that many of our historical teachers placed before us, are largely missing in the current practice of education, which is single-mindedly focused on equipping students with quanta of information and skills, however useful, so that they can be successful in their jobs and careers. Instructing students to become proficient in knowledge and skills acquisition is not the same as educating them (Bai et al., 2009, pp. 323, 324). It is the type of education that entrenches the alienated or objectified consciousness that Bai and her colleagues describe. Their concerns, and those of other educators, are I believe, at the heart of reforms we are currently seeing in education, including: Student-Centered Education, programs dedicated to enhancing resilience, Mindful Leadership, Somatic and Affective Education, Enactivism, Transformative and Integral Education, programs involving Positive Psychology and Emotional Intelligence, and Contemplative Education. My belief is that Contemplative Education is primary in these approaches as its practices can heighten the self-awareness and ability to focus that the others require. While the negative impacts on Education from Cartesian thinking and our hyper-materialist culture cannot all be resolved by contemplation, for this requires systemic change, engaging its benefits as they’ve been outlined is vitally important for students and teaching suffering from increasing pressures and workloads.

The outcome for education they suggest is that, “the larger visions of education that many of our historical teachers placed before us, are largely missing in the current practice of education, which is single-mindedly focused on equipping students with quanta of information and skills, however useful, so that they can be successful in their jobs and careers. Instructing students to become proficient in knowledge and skills acquisition is not the same as educating them (Bai et al., 2009, pp. 323, 324). It is the type of education that entrenches the alienated or objectified consciousness that Bai and her colleagues describe. Their concerns, and those of other educators, are I believe, at the heart of reforms we are currently seeing in education, including: Student-Centered Education, programs dedicated to enhancing resilience, Mindful Leadership, Somatic and Affective Education, Enactivism, Transformative and Integral Education, programs involving Positive Psychology and Emotional Intelligence, and Contemplative Education. My belief is that Contemplative Education is primary in these approaches as its practices can heighten the self-awareness and ability to focus that the others require. While the negative impacts on Education from Cartesian thinking and our hyper-materialist culture cannot all be resolved by contemplation, for this requires systemic change, engaging its benefits as they’ve been outlined is vitally important for students and teaching suffering from increasing pressures and workloads.

For Further Information:

I offer mentoring, teaching, lecturing, workshops and curriculum development in Contemplative Education, and the design of appropriate methods to develop and initiate an institution wide contemplative orientation. To discuss these services please contact me.

References:

(Please note these are the references for this ‘Introduction to Contemplative Education’ and the section on ‘Reasons to Engage and Incorporate Contemplative Education’)

- ADAA. Facts. Retrieved from http://www.adaa.org/finding-help/helping-others/college-students/facts

- Australia, U. (2014). Mental health month at USNW newsletter. Retrieved from https://student.unsw.edu.au/sites/all/files/page_file_attachments/Mental%20Health%20Month%20is%20October%20newsletter%203.pdf

- Bai, H., Scott, C., & Donald, B. (2009). Contemplative pedagogy and revitalization of teacher education. Alberta Journal of Educational Research, 55(3), 319-334.

- Begg, A. (2013). Interpreting enactivism for learning and teaching. Education Sciences & Society, 4(1), 81-96.

- Bennett, S., Maton, K., & Kervin, L. (2008). The 'digital natives' debate: A critical review of the evidence. British Journal of Educational Technology, 39(5), 775-786.

- Bingimlas, K. (2009). Barriers to the successful integration of ICT in teaching and learning environments: A review of the literature. Eurasia Journal of Mathematics, Science & Technology Education, 5(3), 235-245.

- Blair, C., & Razza, R. (2007). Relating effortful control, executive function, and false belief understanding to emerging math and literacy ability in kindergarten. Child Development, 78(2), 647-663.

- Bush, M. (2010). Contemplative higher education in contemporary America. Retrieved from Amherst, Massachusetts:

- CCMIS. Our vision. Retrieved from http://www.contemplativemind.org/about/vision

- CCMIS. The tree of contemplative practice. Retrieved from http://www.contemplativemind.org/practices/tree

- Coburn, T., Grace, F., Klein, A., Komjathy, L., Roth, H., & Simmer-Brown, J. (2011). Contemplative pedagogy: Frequently asked questions. Teaching Theology and Religion, 14(2), 167-174.

- Davidson, R., Dunne, J., Eccles, J., Engle, A., Greenberg, M., Jennings, P., . . . Vago, D. (2012). Contemplative practices and mental training: Prospects for American Education. Child Development Perspectives, 6(2), 146-153.

- Davidson, R., Lutz, A., Slagter, H., & Dunne, J. (2008). Attention regulation and monitoring in meditation. Trends in Cognitive Science, 12(4), 163-169.

- Davis, D., & Hayes, J. (2011). What are the benefits of mindfulness? A practice review of psychotherapy-related research. Psychotherapy, 48(2), 198-208.

- Ghaith, G. (2010). An exploratory study of the achievement of the twenty-first century skills in higher education. Education and Training, 52(6/7), 489-498.

- Greenberg, M., Jennings, P., Rome, D., & Kleiner, A. (2008). Garrison Institute Report: Envisioning the future of contemplative education. Retrieved from Garrison, NY:

- Gregoire, C. (2014). Actually TIME, this is what the 'Mindful Revolution really looks like. Retrieved from http://www.huffingtonpost.com.au/2014/02/04/this-is-proof-that-mindfu_n_4697734.html?ir=Australia

- Gunnlaugson, O. (2011). Advancing a second-person contemplative approach for collective wisdom and leadership development. Journal of Transformative Education, 9(1), 3-20.

- Hart, T. (2004). Opening the contemplative mind in the classroom. Journal of Transformative Education, 2(1), 28-46.

- Hart, T. (2008). Interiority and Education: Exploring the Neurophenomenology of contemplation and its potential role in learning. Journal of Transformative Education, 6(4), 235 - 250.

- Hölzel, B., Carmody, J., Vangel, M., Congleton, C., Yerramsetti, S., Gard, T., & Lazar, S. (2011). Mindfulness practice leads to increases in regional brain gray matter density. Psychiatry Research: Neuroimaging, 191, 36-43.

- Humburg, M., Velden, R., & Verhagen, A. (2013). The employability of higher education graduates: The employers perspective. Retrieved from

- Hyland, T. (2015). The limits if mindfulness: Emerging issues for education. British Journal of Educational Studies, 1-22.

- Jha, A. (2007). Mindfulness meditation modifies subsystems of attention. Cognitive, Affective & Behavioral Neuroscience, 7(2), 109-119.

- Kerr, C. (Producer). (2012, 21/03/2012). The Neuroscience of somatic attention: A key to unlocking a foundational contemplative practice for educators. Webinars. Retrieved from http://www.contemplativemind.org/archives/297

- Lazar, S., Kerr, C., Wasserman, R., Gray, J., Greve, D., Treadway, M., . . . Fischl, B. (2005). Meditation experience is associated with increased cortical thickness. NeuroReport, 16, 1893-1897.

- Leonard, A. (2014). Rise of the phone zombies: What we lose when technology gives us everything. Salon. Retrieved 02/11/2015, http://www.salon.com/2014/08/08/rise_of_the_smartphone_zombies_what_we_lose_when_technology_gives_us_everything

- Moore, A. (2009). Meditation, mindfulness and cognitive flexibility. Consciousness and Cognition, 18(1), 176-186.

- Morgan, P. (2012). Following contemplative education students' transformation through their 'ground-of-being' experiences. Journal of Transformative Education, 10(1), 42-60.

- Morgan, P. (2015). A brief history of the current reemergence of contemplative education. Journal of Transformative Education, 13(3), 197-218.

- Oh, E., & Reeves, T. (2014). Generational differences and the integration of technology in learning, instruction, and performance. In D. Jonassen (Ed.), Handbook of research on educational communications and technology (pp. 819-828). New York, NY: Springer.

- Palmer, P. (2014). Forward. In D. Barbezat & M. Bush (Eds.), Contemplative practices in higher education. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

- Pelgrum, W. (2001). Obstacles to the integration of ICT in education: Results from a worldwide educational assessment. Computers & Education, 37(2), 163-178.

- Robels, M. (2012). Executive perceptions of the top 10 soft skills needed in today's workplace. Business Communication Quarterly, 75(4), 453-465.

- Robinson, L., Magee, C., Safadi, M., & Sharma, R. (2014). Health profile of Australian employees. Retrieved from http://www.workplacehealth.org.au/announcements/whaa-report-on-health-profile-of-australian-workers-released

- Roeser, R., & Peck, S. (2009). An education in awareness: Self, motivation, and self-regulated learning in contemplative perspective. Educational Psychologist, 44(2), 119-136.

- Shapiro, J., Brown, K., & Astin, J. (2008). Toward the integration of meditation into higher education: A review of research evidence. Teachers College Record, 113, 493-528.

- Shapiro, S., Schwartz, G., & Bonner, G. (1998). Effects of mindfulness-based stress reduction on medical and premedical students. Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 21(6), 581-599.

- Twenge, J. (2006). Generation ME: Why today's young Americans are more confident, assertive, entitled - and more miserable than ever before. The Free Press.

- Vines, P. (2014). Law S1052, Introducing law and justice - Session 1, 2014. University Course. UNSW. Sydney, Australia.

- Waxler, R., & Hall, M. (2011). Transforming literacy: Changing lives through reading and writing (Vol. 3). WA, UK: Emerald Books.

- Zajonc, A. (2013). Contemplative pedagogy: A quiet revolution in higher education. New Directions for Teaching and Learning, 134, 83-94.

- Zeidan, F. (2010). Mindfulness meditation improves cognition: Evidence of brief mental training. Consciousness and Cognition, 19, 597-605.

- Zeidan, F., Johnson, S., Diamond, B., David, Z., & Goolkasian, P. (2010). Mindfulness meditation improves cognition: Evidence of brief mental training. Consciousness and Cognition, 19, 597-605.